There is nothing the media and the public, any public, love more than a good sob story. A sick kid who needs an organ, the local teacher who goes beyond the call of duty, the hard-done by battler fallen on hard times.

Pundits, analysts and China watchers tend to focus on the country’s economic miracle, its complex politics and the impact these will have on the wider world.

As a journalist I have always been more interested in the human stories. They are often dismissed as ‘soft news’ but to my mind, the stories a country tells itself about it’s people can reveal more about a national mindset than any set of statistics.

And few places consume tales of woe with as much fericous enthusiasm as China.

Sick mothers, generous migrant workers, filial children caring for ailing parents – tales of heroism and self sacrifice are never in short supply.

But the human interest stories from China that make headlines in the West are often of shocking indifference and cruelty. Many will recall the story of YueYue, the 2-year old girl in Foshan who was run over by a truck and lay injured by the road, ignored by passer-bys until, finally, the 19th person to walk past went to her aid. Or the Daily Mail favourite, Eagle Dad, the father who forced his 4-year old son to run in the snow to toughen him up. Those stories made headlines around the world and fed into some unfortunate stereotypes about Chinese.

In China those stories prompted much soul searching and debate on whether the country was in a ‘moral vacuum’. But the big “human interest” stories of the past year, the ones that didn’t make headlines outside of China, paint a far more complex picture.

When Beijinger Fan Meng discovered his wheelchair-bound mother always dreamt of visiting Xishuangbanna in Yunnan province he decided to take her there. On foot. Pushing her wheelchair, Fan and his mother traversed the country, spending three months to reach their destination on the adventure of a lifetime. They were accompanied by the family dog, Butterfly.

Li Boya, 20, was training to be a railway policeman when he jumped onto the tracks to stop a man from committing suicide, he lost both his legs but swears he would do it again if it would save a life. Middle-school teacher Zhang Lili, 29, was already popular in her school, quietly giving disadvantaged students money from her own salary to pay for books. But she became a national hero when she pushed two of her students out of the way of an oncoming bus only to be run over herself, losing both her legs.

The yarn that really struck me, however, was that of Fu Xuepeng.

In 2006, when he was 23, Fu was in a motorcycle accident which left him paralyzed and unable to breathe unassisted. His parents, unable to afford medical care, rigged up a homemade respirator they could operate by hand. To keep their son alive they took turns to manually pump the device – 24 hours a day seven days a week. They were occasionally helped by friends and neighbours. Even so, their hands became deformed from their efforts.

After two years of this, they managed to rig up a simple mechanical device to pump the respirator, but unable to afford the electricity to keep it operating around the clock, they only turned the machine on at night, continuing to hand pump the respirator by day.

“No parents would give up on their child as long as there is a slight chance of living.” the young mans father, Fu Minzu, told state media.

When the media picked up Fu’s story a company stepped in to donate a state of the art respirator. Donations flooded in to pay Li and Zhang’s medical expenses. Donations for Zhang, who has been dubbed “the most beautiful teacher in China” are reported to be in excess of 11 million yuan ($AUS 1.68 million).

Fan and his mother were greeted in Xishuangbanna after three months of walking by a crowd of residents who read their story in the media and, oddly, a few elephants.

While as a journalist I can appreciate the news value in each of these stories – they certainly would have made big news in just about any country – it seems China has a particular appetite for a tragic hero, a person who sacrifices themselves for the greater good. While the Australian narrative tends to love the underdog, Steven Bradbury is a particularly Aussie kind of legend, China likes their heroes, well, heroic. Which is why I was interested to learn of Lei Feng.

Lei was an orphan who joined the People’s Liberation Army when he was 20. A year later, in 1962, he was killed by a falling telephone pole that had been hit by a truck.

So far, so unremarkable.

Except a year later Lei’s diary, detailing the good deeds this everyman soldier carried out on a daily basis, was released to the public – the start of a massive propaganda campaign. The story went that Mao Zedong handpicked Lei to be an example for the Chinese people, and the phrase “Learn from Comrade Lei Feng” became a rallying cry.

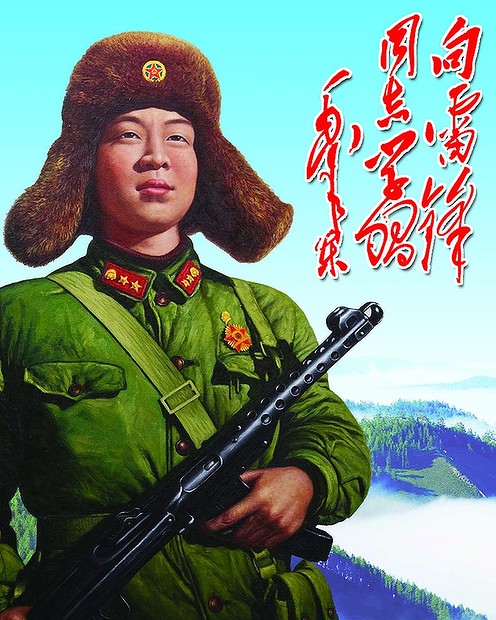

A typical propaganda poster of Lei Feng, the script is in Mao’s hand and reads “Learn from Comrade Lei Feng”

Children at school woud keep a diary, just like Lei Feng, where they detailed their good deeds. The slogan “Learn from Comrade Lei Feng” was emblazoned across the country. March 5 is still “Learn from Lei Feng Day,” and state media run stories of Chinese who solemnly swear they are doing charity work to be more like Lei Feng.

Lei Feng was essentially created to become a national folk hero in the communist mould, a Chinese Don Bradman and Ned Kelly rolled into one, but without the anti-authoritarianism at the core of so many Australian legends. He lived a life of virtue, left documents describing his good deeds and was conveniently dead, allowing people with vested interests to twist his lagacy to suit their own ends. “Learn from Comrade Lei Feng is essentially the Chinese version of What Would Jesus Do?

But is any of it true?

While a guy called Lei Feng probably existed, whether he was some kind of saint or not remains dubious. One big give away is the series of strangly posed pictures of Lei Feng doing good deeds. A nobody orphan PLA agent helps a little old man or reads to a bunch of kids and a photographer just HAPPENS to be there to capture the moment? Remarkable.

While Lei Feng day is still celebrated, most Chinese today are more than a little skeptical about this ’60s propaganda tool, but the concepts embodied by Lei Feng are still around – just open a newspaper. Unlike in the West, the stories of Fan, Fu, Li and Zhang are not just great newspaper yarns, but focal points for national soul searching. Is Fan’s devotion to his mother show filial spirit is still alive and well in China? Is the prediciment faced by Fu and his parents simply a demonstration of touching devotion by parents to their son or a shocking example of the widening wealth gap? Does Li and Zheng putting their lives on the line to save others show that Chinese people are still willing to sacrifice themselves for the greater good? These are the topics debated online when these stories break in mainstream media. These stories are not just about a woman who lost her legs, or parents who are trying to keep their son alive, they are snap shots of today’s China and their meaning and significance are shaping what it means to be Chinese.

Great work Belle…does anybody ever just lose one leg doing a brave deed or is that considered not quite heroic enough?

Thanks for providing a little balance to the coverage we so often get here in Australia.